Bathurst, N.B. ranks eighth in Canada among places with high concentrations of older residents

Exodus of young people creates challenges for older adults struggling to find healthcare and other services

By Carly Penrose and Breanna Schnurr

Local News Data Hub

Feb. 7, 2024

The golden years are not all golden in Bathurst, N.B., where 36 per cent of residents are 65 or older, more than in almost any other urban area in Canada.

Harsh winters, lack of public transit and soaring dementia rates are challenging realities for older people in the city, which has the eighth-highest concentration of older adults in the country, according to a new analysis by the Local News Data Hub at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU).

Anne Theriault, 73, said she loved growing up in Bathurst, a community of just over 12,000, but sees few advantages to aging there apart from knowing so many people.

She said she is already worried about finding a replacement when her family doctor retires in about five years. Statistics Canada data show that Bathurst is in a health region where 5.5 per cent of people 65 or older do not have a family doctor.

Theriault, whose two children have moved away, said she and her husband struggle to find help with household chores. “I’ve talked to different people who are widowed or circumstances change and [they] are not physically able to do things,” she said. “They need help and they just can’t find it.”

There’s also not much for older people to do, Theriault said. She was part of a group that organized sock-hop dances to raise money for charity but said it “fell apart” when the pandemic hit.

Bringing people together is complicated by the lack of public transit, which forces many to rely on taxis, friends or family for rides, Theriault said.

Stephen Brunet, a local councillor and former Bathurst mayor, acknowledged that getting old in the community comes with challenges.

Residents with walkers or electric wheelchairs are out in good weather, he said. But Bathurst can get more than three metres of snow during its long winter, making it difficult for people with mobility challenges to leave their homes and get around.

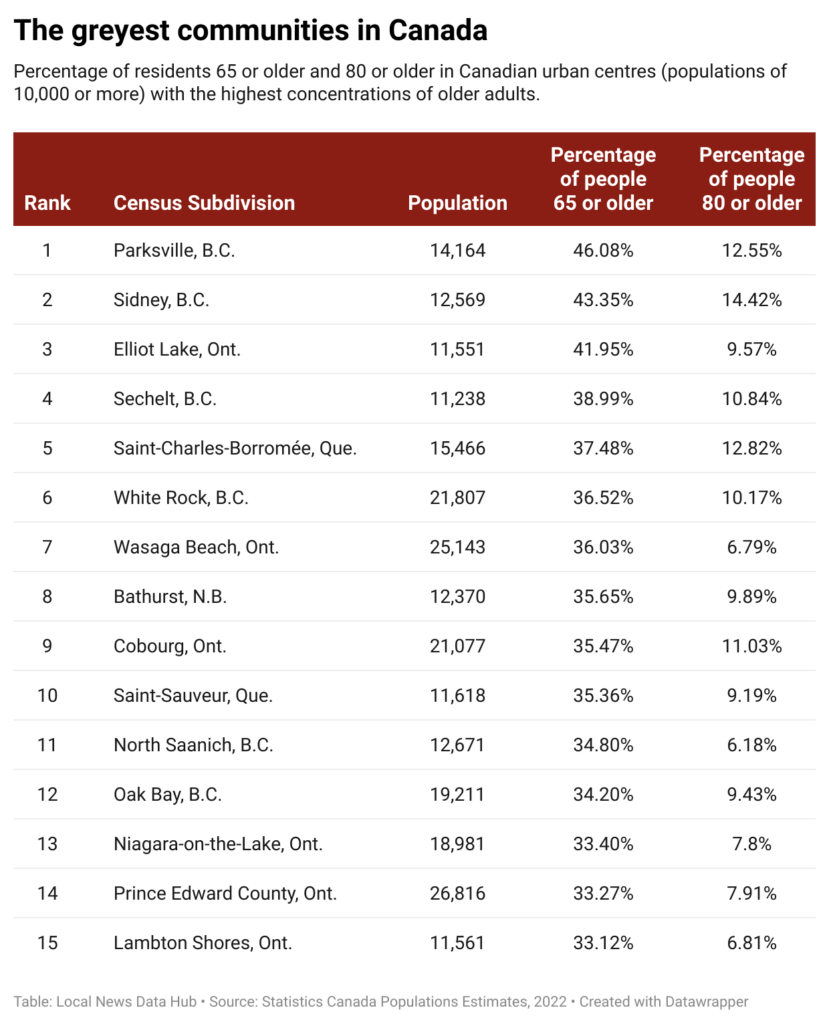

Bathurst isn’t the only municipality grappling with the challenges of an aging population. The Local News Data Hub identified 111 urban centres in Canada where at least a quarter of residents are 65 or older. The analysis, which ranked communities based on the percentage of older residents, focused on places with at least 10,000 people because that loosely aligns with what Statistics Canada considers the minimum population for an urban centre.

Dr. Samir Sinha, an internationally recognized geriatrician and director of health policy research at TMU’s National Institute on Aging, said the needs of older adults change over time.

“People tend to be able-bodied, healthy and independent in the first decade after retirement,” said Sinha, who is also director of geriatrics at University Health Network hospitals in Toronto.

Retired people, he added, may be drawn to more affordable communities or idyllic places. As they age, however, these same places can become “an absolute nightmare” in the absence of adequate health-care and other services.

Nationally, the share of Canada’s population that is 65 or older jumped to 19 per cent in 2022, from 14 per cent in 2010. Statistics Canada estimates that number will rise to nearly 25 per cent by mid-century.

The growing number of older Canadians poses additional challenges for municipalities facing what the Alzheimer Society of Canada says will be a “staggering” increase in dementia cases: In 2020, 8.4 per cent of Canadians over 65 had some form of dementia. By 2050, it is forecast to be 13.2 per cent.

Already in Bathurst and the neighbouring communities of Beresford and Petit-Rocher, 11.5 per cent of people say they or someone in their household has memory problems, according to 2020 data from the New Brunswick Health Council.

Demand for care, meanwhile, is outstripping supply. Brunet said the city has a number of fairly new, well-equipped nursing homes, but there are “still quite a few people in the hospital waiting for a placement.”

The high proportion of older people in Bathurst is driven, in part, by a recent influx of older, out-of-province newcomers drawn by the picturesque Chaleur Bay and the city’s relatively affordable housing prices.

But young people have also been leaving New Brunswick for years, said Michael Haan, academic director of the Statistics Canada Research Data Centre at Western University in Ontario. They have long been told “if you want to make it, you’ve got to get out.”

Haan, who used to work at the University of New Brunswick, said youth emigration in the early 2000s meant Bathurst was one of the first communities in Canada to have more people over 65 than under 15. The consequences include doctor, nurse and other labour shortages that could worsen in the coming years, he warned.

The Local News Data Hub used Statistics Canada’s 2022 population estimates to build the community ranking, which was reviewed by Sebastien Lavoie, a senior analyst at the Statistics Canada Centre for Demography. The analysis also found that:

- The municipalities with the highest concentrations of residents 65 or older tend to be smaller — 87 of the 111 communities on the Data Hub’s list have fewer than 30,000 residents.

- Doctor shortages are a reality in many municipalities with large cohorts of older adults. Statistics Canada data showed that in 2020, just under a third (33) of the 111 places on the list are in health districts where at least 10 per cent of people 65 or older don’t have access to a family doctor. Nationally, it is 5.9 per cent.

- After Bathurst, the next Atlantic Canadian municipality on the list was 22nd-ranked Queens, N.S., where just under 32 per cent of the population is 65 or older.

- Two Vancouver Island communities topped the list. In first-ranked Parksville, B.C., 46 per cent of the 14,000 residents are older adults, while in second-place Sidney, B.C., they make up 43 per cent of the population.

- Elliot Lake — a northern Ontario mining-town-turned-retirement-community — ranked third. Forty-two per cent of its approximately 11,000 residents are 65 or older.

Experts point to a variety of ways communities can be more age-friendly.

Sinha’s to-do list for local governments includes ensuring older residents can get around without a car. People outlive their decision to stop driving by 10 years on average, he noted. “How do they continue to get to the grocery store? How do they continue getting out to other activities and…connect with their friends and family?”

Sinha said age-friendly communities need public spaces with bathrooms and benches with armrests so it is easier to sit and get up.

Streets can also be made safer, he added, with changes such as extended crossing times at intersections. Statistics Canada data show that pedestrians over 70 are more than twice as likely to be killed in traffic incidents than pedestrians in any other age group.

International examples of age-friendly adaptations are also instructive. In Denmark, municipalities conduct home visits to identify older people needing care. In Singapore, families receive a housing grant for living near elderly relatives. France’s Paris Solidaire connects older adults with young people as roommates to share rent and provide companionship.

Closer to home, Vancouver International Airport offers sunflower lanyards to travellers with a cognitive impairment. This makes it easier for airport staff, who are trained in disability and dementia awareness, to identify and accommodate them.

The Alzheimer Society of New Brunswick, meanwhile, publishes guidelines for creating dementia-friendly indoor spaces that include using low-pattern carpeted floors because shiny floors can look wet and cause confusion.

This story was produced by the Local News Data Hub, a project of the Local News Research Project at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Journalism. The Canadian Press is the Data Hub’s operational partner. Detailed information on the data and methodology can be found here.