Doctor shortage casts a pall on Parksville, B.C., Canada’s ‘greyest’ city

Four B.C. municipalities rank high on list of places with largest percentage of older residents, analysis finds

By Carly Penrose and Breanna Schnurr

Local News Data Hub

Feb. 7, 2024

The golden years are not all golden in Parksville, B.C., where residents 65 and older make up 46 per cent of the population, more than in any other urban area in the country.

The Vancouver Island community of about 14,000 people is a magnet for older Canadians who say they love the mild weather, outdoor activities and beautiful surroundings. As they age, however, many are discovering that doctor shortages, limited public transit and soaring dementia rates are also part of the Parksville package.

Municipal councillor Sylvia Martin said the city is a draw for younger retired people but “when they get really old, they move back to be closer to where they’re from” for family support and more accessible health care.

The local doctor shortage is a major “downfall” in a place that otherwise has much to offer older adults, Martin said.

In the Central Island Health Service Delivery Area, which includes Parksville, Statistics Canada data show that 5.3 per cent of people 65 or older don’t have a family physician. That’s slightly better than the national rate of 5.9 per cent, but even so “we have people every week contacting us saying they [haven’t had] a doctor for two years.”

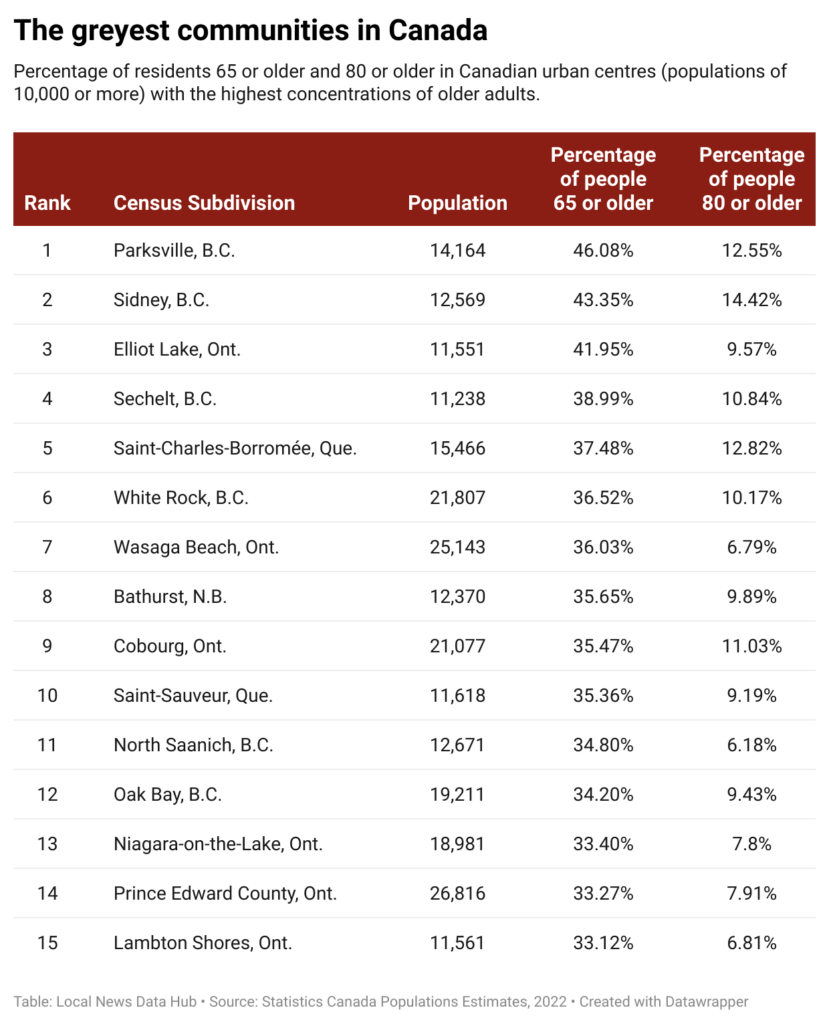

Parksville topped a list of the 111 urban centres in Canada with the highest concentrations of older residents, according to an analysis by the Local News Data Hub at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU). The analysis, which ranked communities based on the percentage of older residents, focused on places with at least 10,000 people because that loosely aligns with what Statistics Canada considers the minimum population for an urban centre.

Dr. Samir Sinha, an internationally recognized geriatrician and director of health policy research at TMU’s National Institute on Aging, said the needs of older adults change over time.

“People tend to be able-bodied, healthy and independent in the first decade after retirement,” said Sinha, who is also director of geriatrics at University Health Network hospitals in Toronto.

Retired people, he added, may be drawn to more affordable communities or idyllic places with great weather. As they age, however, these same places can become “an absolute nightmare” in the absence of adequate health-care and other services.

Leaving Parksville is not in the cards for Jeanette Mossing, who is in her 90s and has lived in the city for six years. She said she loves walking the local trails with her two dogs.

She admits, however, that the city has its shortcomings. Mossing, who doesn’t drive, said she relies on “kind people” in her circle for transportation because there is no local public transit. Regional buses provide access to the nearest hospital in Nanaimo, B.C., about a 35-minute drive away, but they only come about once per hour and Mossing says many stops don’t have places to sit.

Mossing also recently became an ‘orphan’ patient after her doctor moved to Vancouver. In her bible study group, she said, “there were about five other people that said they lost the same doctor.” She now takes her health concerns to the local urgent care centre, where it can take hours to get medical attention.

Nationally, the share of Canada’s population that is 65 or older jumped to nearly 19 per cent in 2022, up from 14 per cent in 2010. That number is expected to stabilize around 25 per cent by the middle of the century.

The growing number of older Canadians poses additional challenges for municipalities facing what the Alzheimer Society of Canada says will be a “staggering” increase in dementia cases.

Nearly 600,000 Canadians are currently living with the condition. By 2030, that number could reach almost one million, according to the Alzheimer Society.

Dementia is already more prevalent in Parksville than in B.C. overall. Data from the province’s Chronic Disease Registry show that in 2020-21, 52.5 in every 1,000 people 40 or older had some form of dementia, compared with 30 per 1,000 provincially.

Meanwhile, wait times for long-term care homes are now up to a year in Parksville, according to Island Health. The provincial average is just over six months.

Blair Gohl, whose wife has dementia, said the high demand for limited services in Parksville means “you basically have to take care of your partner.”

The Local News Data Hub used Statistics Canada’s 2022 population estimates to build the community ranking, which was reviewed by Sebastien Lavoie, a senior analyst at the Statistics Canada Centre for Demography. The analysis also found that:

- The municipalities with the highest concentrations of residents 65 or older tend to be smaller — 87 of the 111 communities on the Data Hub’s list have fewer than 30,000 residents.

- Doctor shortages are a reality in many places with large cohorts of older adults. Statistics Canada data showed that in 2020 just under a third (33) of the 111 municipalities are in health districts where at least 10 per cent of older adults don’t have access to a family doctor. That compares to 5.9 per cent for Canada as a whole.

- Sidney, B.C., also on Vancouver Island, was second in the ranking after Parksville. Older adults make up 43 per cent of the town’s population. Sidney also stands out for having the highest proportion of people who are at least 80: More than 14 per cent of residents have had an 80th birthday, compared to 4.5 per cent of all Canadians.

- Two other B.C. communities rank near the top of the list. In fourth-place Sechelt, where 39 per cent of people are older adults, was fourth. Meanwhile, 36.5 per cent of residents in White Rock, near Vancouver, have turned 65.

- Although 56 per cent of residents in Qualicum Beach, B.C., near Parksville, are at least 65, the community was not included in the nationwide ranking because its population fell just short of the 10,000-person threshold used for the analysis.

Experts point to a variety of ways communities can be more age-friendly.

Sinha’s to-do list for local governments includes ensuring older residents can get around without a car. People outlive their decision to stop driving by 10 years on average, he noted. “How do they continue to get to the grocery store? How do they continue getting out to other activities and…connect with their friends and family?”

Sinha said age-friendly communities need public spaces with bathrooms and benches with armrests so it’s easier to sit and get up.

Streets can also be made safer, he added, with changes such as extended crossing times at intersections. Statistics Canada data show that pedestrians over 70 are more than twice as likely to be killed in traffic incidents than pedestrians in any other age group.

International examples of age-friendly adaptations are also instructive. In Denmark, municipalities conduct home visits to identify older people needing care. In Singapore, families receive a housing grant for living near elderly relatives. France’s Paris Solidaire connects older adults with young people as roommates to share rent and provide companionship.

Closer to home, Vancouver International Airport offers sunflower lanyards to travellers with a cognitive impairment. This makes it easier for airport staff, who are trained in disability and dementia awareness, to identify and accommodate them.

The Alzheimer Society of New Brunswick, meanwhile, publishes guidelines for creating dementia-friendly indoor spaces that include using low-pattern carpeted floors because shiny floors can look wet and cause confusion.

This story was produced by the Local News Data Hub, a project of the Local News Research Project at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Journalism. The Canadian Press is the Data Hub’s operational partner. Detailed information on the data and methodology can be found here.